Remembering the Telegraphist Air Gunners

copyright © Wartime Heritage Association

Website hosting courtesy of Register.com - a web.com company

Wartime Heritage

ASSOCIATION

William (Bill) George West

Telegraphist Air Gunner, Fleet Air Arm, Royal Navy

William (Bill) George West was born on January 8, 1925 in Stockport, twelve miles from Manchester in Cheshire, a northern

England industrial town with both cotton mills and hat factories. His mother was a milliner, his father a mill manager and formerly a

soldier of the British Army in India. Bill was one of two sons. A brother, Tony, was born when Bill was seventeen. During the war

Tony was little, and whenever he saw a plane going over, he thought it was Bill.

Stockport was a Roman fortress town and historically one of the oldest Roman centres in England.

“When I was a boy there were still Roman cobbled streets/roads about including our main road

fully cobbled 'five chariots wide' running through our town centre from London to the North. We

had the Stockport Tram Lines on the cobbles! The trams have gone now and so have the cobbles

but the authorities have kept some sections for heritage reasons.”

“I had a happy childhood. I went to church and Sunday school at St. Mathews, Edgeley, became a

Cub and later a Boy Scout, and a member of the Air Training Corps.” Bill attended Stockport

School and left school at age fifteen.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, with so many men enlisted in the services, there was no shortage

of jobs for a young man. Bill applied for and received a position with the LMS Railways. The

Company sent him back to part time school at Stockport College to become a bookkeeper but Bill

joined up before he finished the course. We experienced air raids on Manchester and Stockport

experienced air raids and Bill, although in the Air Training Corps was a messenger in the Auxiliary

Fire Service.

“The industries of Manchester had been severely bombed and some of the over-bombing struck parts of Stockport. There were

many casualties and in most of our minds there was a distrust and even hatred of the enemy, so many of us were volunteers before

our call up dates.”

“When World War II broke out my home town of Stockport had at least a dozen cinemas and my suburb of Edgeley had two and

most folk went to the pictures. Just before I was eighteen in 1942, I went to the Alexandra Cinema and watched a war film about

the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm and what its ‘birdies’ did. I was already impressed with the Fleet Air Arm, but as I was nearing call up

and it was said that volunteering got you into the unit of choice, I volunteered and applied to join the Royal Navy as aircrew in the

Fleet Air Arm.”

Just before turning eighteen, Bill received a letter from the recruiting office with orders to report to the Air Crew Selection Board

at Crewe in Cheshire. An interview and medical followed.

“I asked to join the Fleet Air Arm as aircrew and after a selection board interview and tests I was accepted to do a Telegraphist Air

Gunners’ course.”

After several weeks and nearing his birthday he got the approval letter and a train ticket to HMS Royal Arthur at Skegness on the

east coast of England. Royal Arthur, the former Butlins Holiday center at the sea-side resort in Skegness had hut accommodations

and was taken over by the Royal Navy at the outbreak of war. As a ‘boot camp’, the new recruits were given the usual sailor’s

uniform and lots of military drill by a Chief Petty officer.

The group was then sent to the cadet training school at HMS Saint Vincent, Gosport, in Hampshire, for air radio and aircrew

regulation training.

After a month at HMS Saint Vincent, Bill was one of those chosen to train at No 1 Air Gunners School at East Camp, Yarmouth, Nova

Scotia in Canada and was sent to a holding base in Glasgow, on the Clyde, to await passage. During the war fifty percent of

Telegraphist Air Gunners were selected to train at East Camp.

The group crossed the Atlantic on the liner RMS Queen Elizabeth from Glasgow to New York. In New York that ship would berth

alongside the French liner Normandie, which was turned over on it side attributed to Nazi sabotage.

They stayed at the Royal Navy service camp at Astbury Park, New Jersey. The camp had been, prior to the war, holiday apartments

for New Yorkers. The Royal Navy barracks comprised two hotels which were fenced and had a center forecourt as a parade ground.

From there the group travelled by train to Boston and to St John, New Brunswick in Canada. From St. John they crossed the Bay of

Fundy to Digby in Nova Scotia on the ferry Princess Helene and by train to Yarmouth.

“The Princess Helene was blacked out because of U-

boat activity and we were told that another ferry, a

sister ship to the Princess Helene, had been sunk most

likely by a mine from a U-boat”

In April 1942, it was reported by intelligence services

that a submarine might try to attack the dry-dock in

Saint John and the Princess Helene. The ferry SS

Caribou, from Sydney to Newfoundland, was sunk on

October 15, 1941 with 137 lives lost. The Princess

Helene made two return trips daily, Between St. John

and Digby. The group of young British lads became

Course 50A at Yarmouth for Telegraphist Air Gunners.

Training went on with very few breaks because of the

weather. Air radio in the Fleet Air Arm had just moved

into RT (radio telephony); however, it was new and WT (wireless telegraphy) for Morse code was still very much used as it had a

much longer range than RT.

“We did ops room training for about eight weeks before we were chosen for flying and sent to the RCAF store to get our

aircrew log book with Royal Canadian Air Force printed on the cover. We trained in Fairey Swordfish with both Royal Air Force and

Royal Canadian Air Force pilots. The course was issued with RCAF aircrew log books, which is the only one I had. The trainee TAG's

did air radio exercises, air to ground plus plane to plane. We had to roll out very long trailing antennae and drag it back. The

trainee also had to wind down and lock the wheel undercarriage for landing.”

Bill’s first flight at East Camp was for wireless training on September 20, 1943 at 0930 hours in a Swordfish piloted by P/O

Hayward. The flight lasted forty minutes. His last training flight was on December 29, 1943. That flight lasted over 8 hours.

“Our 'passing out' certificates were in the form of regulation cloth/paper record forms headed "History Sheet for Telegraphist

Air-Gunner and Rating Observer" with all our examination results listed. We had to immediately hand them back to the Writers'

Office and we were formally presented with TAG Wings which we wore on the left cuff.”

Like many of the young British TAGs training at East Camp, Bill made friends

with people in Yarmouth.

“I recall the Lake Milo Yacht Club and

taking Betty Miller to a dance there

(or she took me). I also recall ice

yachts on Lake Milo after a big

freeze, fridges were not around in

those days, but many Yarmouth folk

had ice chests and I do recall a

Yarmouth ice company cutting huge

portions of ice and burying that cut

ice for sale later on.”

Another memory I recall was that

Helen Gavel worked in the

Woolworth Store on the main

street.”

At eighteen years of age, Bill was

confident and outgoing. He spent time at the Gavel farm in Richfield

travelling by the train from Yarmouth to Richfield and de-training in the village of Hectanooga in Digby County.

The village lies in rural Nova Scotia beyond Richfield. There he worked in the hay during the summer of 1942, spent time walking

the wooded road to the river and relaxing away from East Camp.

On completion of his training George Gavel and his wife Cleta gave Bill a copy of the Bible which he still has among his belongings.

Cleta Gavel corresponded with Bill’s mother in England during the war.

Bill returned to Britain and Lee-on-Solent, after his TAG training, on the Dutch liner New Amsterdam from Halifax, Nova Scotia. He

had seven operational training flights from the Fleet Air Arm Station at Lee-On-Solent before temporarily joining 826 Squadron.

For the next four years Bill was with 820 Squadron assigned to HMS Indefatigable spending time both in the Atlantic and Pacific

campaigns

He was sent to the Royal Navy Airs Station in Crail Scotland for Ops training in Barracudas. He never managed to fly in the

Barracuda because 826 Squadron within a few weeks of his arrival was merged into 820 which flew Grumann Avengers.

Down with a bad case of the flu he didn’t participate when 826 Squadron flying Barracudas went to sea to attack the German

battleship Tirpitz in Alten Fiord Norway in Operation ‘Goodwood IV’ during August 1944.

Training in Avengers was completed at the Royal Navy Air Station Kirkwall, in the Orkney Islands. 820 Squadron then rejoined the

HMS Indefatigable with the new Avengers and with the rest of the British Pacific Fleet sailed for the Indian Ocean and then into the

Pacific Ocean.

There were twelve more advanced training flights from the Royal Navy Air Station HMS Ukussa in Ceylon in the district of

Katakarunda not far from Colombo. These training flights were flown off the Indefatigable in December 1944.

Squadrons from HMS Indefatigable and other aircraft carriers of the British Royal Navy Pacific Fleet led air strikes against the

Japanese held oil refinery at Medan on January 4, 1945, and against the Japanese held Dutch Oil refinery at Palambang on

January 24 and 29, 1945. On the 29th, the final day of operations, having made the two hundred mile flight from the carriers over

ocean and the jungle terrain of Sumatra, the British Avengers came under heavy attack from Japanese Zero fighters and ground

artillery.

“Just before our Grumann Avenger got to the target we lost engine

revs and couldn't keep up with the main strike force. We were still flying

on course but we observed Japanese Army buildings that were not far

from the general target area. To lose a lot of weight we bombed the new

target then started to limp back to the Indefatigable on our own. We

were fortunate not to meet any Zeros. We had flown from the Indian

Ocean side of Sumatra to the target area on the other side. Getting back

all on our own was dicey.”

Following the Palambang strikes HMS Indefatigable sailed for Sydney

Australia where several destroyers from the Royal Australian Navy joined

the larger Royal Navy Aircraft Carriers as escort. HMAS Quiberon became

attached to HMS Indefatigable. Earlier HMAS Quiberon had picked up

some downed flyers from 820 Squadron after an encounter with the

Japanese Air Force.

Sydney, Australia became the home port for the largest fleet ever

assembled by the Royal Navy. That fleet included battleships, cruisers,

destroyers, tankers, supply ships, minesweepers as well as several light

fleet carriers, an aircraft repair carrier, and former merchant ships fitted

with flight decks called auxiliary or MAC (merchant aircraft carrier)

ships. Among the five aircraft carriers was HMS Indefatigable. The fleet

was made up of warships from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South

Africa, and France.

The Pacific Fleet moved on to Sumatra and carried out strikes on the Sakishima Islands and Japan itself. Until the landings at

Okinawa the task assigned the British Pacific carriers was to attack Japanese airfields on groups of Japanese islands called The

Sakishima Gunto and the Ryuku Islands.

Prior to those attacks, 820 Squadron carried out operations against small shipping in Hirara Harbour, Myoko Jima, south of Japan.

“After Palambang the Squadron made strikes against small Japanese shipping in Hirara Harbour on Myoko Jima south of Japan. This

raid was on March 27, 1945. It was successful and a few days later we sensed there was a Japanese sub some where checking us

out. We did a checkered anti sub patrol with others of the squadron with no result. This was on March 30, 1945. On the next day

we did a strike on the Japanese airfields on Ishigake. Our aim was to wreck the runways and this we did. We were successful with

raids on shipping in all parts of the Sakishima Gunto. Similar raids took place on April 7th, 10th, 13th, 15th, 17th, and on the

29th.”

On Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945 the British fleet carriers had flown off their first fighter strike when Japanese aircraft were

detected by radar seventy-five miles to the eastward, closing in on the fleet at 210 knots at a height of 8000 feet. Low cloud and

consequent poor visibility gave initial advantage to the Japanese, who split their formation some forty miles from the fleet.

The ships were firing at the enemy aircraft when a Kamikaze bomber carrying a 250-kilogram bomb came out of the clouds and

attacked HMS Indefatigable. The plane crashed across the carrier flight deck.

“I was on board when the Kamikaze plane hit the after end of the Island Control unit rear of the bridge where the island sick bay is

situated and finished exploding on the flight deck alongside. A few aircraft were damaged but four officers and ten ratings were

killed and sixteen others were wounded. The sick bay was empty except for the doctor on duty who was killed in the attack. He

was a Canadian doctor on loan to the Royal Navy.”

The Canadian, twenty-nine year-old Dr. Alan McCarthy Vaughan (Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve) was serving as a Surgeon

Lieutenant aboard HMS Indefatigable.

“The British aircraft carriers had armour plate steel flight decks unlike the United States carriers that had wooden flight decks.

While this gave them a somewhat larger ship with more aircraft than the British carriers, those wooden decks were an ideal target

for kamikazes.”

Bill participated in eleven strikes on the Japanese including one anti submarine search. On his last operation, April 29, 1945, his

aircraft didn’t quite land smoothly on the aircraft carrier. He was thrown forward and his face injured. Initially, he was taken to

sick bay and the facial injury bandaged; however, the following day it was discovered the injury was more serious. After Bill passed

out and once again found himself in sick bay, a decision was made to return him on a hospital ship to Sydney, Australia.

Sydney, Australia became a favourite place for R&R. Various centres were established in the city to provide allied service

personnel with meals and recreation. Freed from the military hospital with a pass, Bill and Denny Vaughn, another TAG, made their

way to the British Service Club in Hyde Park.

Gwen Jamieson, a Sydney girl, was employed at the T & G Insurance Co. She had answered a request posted

on a notice board at work to young Sydney women to go to the British Service Club to help welcome young

English service men. Her first night at the Centre in mid 1945 she met Bill West.

After that first meeting in the early part of 1945, they met every night as he had a leave pass for every

second night and a very good copy of a leave pass for every other night. Bill became a constant visitor at

Gwen’s house. He went to church with her and enjoyed the involvement and friendship of her family.

Bill had to ask the permission of the captain of the Indefatigable marry Gwen, and she had to go for an

interview to determine that she was suitable. The British Navy was impressed with Gwen, a school teacher’s

daughter who had graduated from high school and was employed with an insurance company.

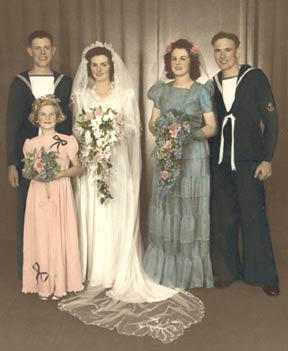

Bill and Gwen were married at Hurlstone Park Baptist Church, Sydney, at 7 p.m. on a Friday night, November 2, 1945.

Bill was involved in some early training of Australian Fleet Air Arm personnel at Schofields in New South Wales. He did not return to

the Pacific Campaign.

In June 1945, HMS Indefatigable and 840 Squadron joined the 7th Carrier Air Group,

and was involved in strikes around Tokyo until the war ended and the carrier returned

to Sydney. Bill returned to England on Indefatigable in January 1946 to leave the Navy

and resume employment in the railway.

In 1946 civilian travel was restricted as the seas were still fraught with danger and it

wasn’t until July 3, 1946 that Gwen sailed from Sydney, one of 655 Australian war

brides of British servicemen, on the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious. Bill met Gwen at

Plymouth on August 7, 1946.

They reunited couple settled down to live on in post-war England. They lived in

Stockport and Gwen worked at W. G. West, a business owned by Bill’s uncle.

Bill decided that post-war England was not as attractive as Sydney and so in the spring

of 1947 Bill and Gwen decided to return to Australia making the trip onboard the SS

Stratheden on its maiden voyage to Australia after conversion from a troopship. They

were on a waiting list and a vacancy occurred three days before sailing. The ship

sailed from Tilbury and arrived at 8:00 am on August 1, 1947 in Sydney Harbour. Gwen was six months pregnant and six weeks after

arrival in Sydney the first of their three daughters was born. On November 2, 2005, Bill and Gwen West celebrated their Diamond

Wedding Anniversary.

Bill had a job organized in Australia working as an apprentice French polisher with family friends who owned a furniture making

business. After three months he obtained employment with BP in a clerical/administrative capacity. Bill continued to work with BP

for thirty-five years until his retirement in 1979.

Also see:

A Journey To Remember - Gwen West (Australian War Bride)

Following in their Father's Footsteps - October 22, 2008

- World War I - Menu

- WWI Stories and Articles

- Photos - Yarmouth Soldiers

- Selection of World War I Songs

- WWI Casualties of Yarmouth, NS

- Those Who Served - Yarmouth, NS

- WWI Casualties Digby Co. NS

- WWI Casualties Shelburne Co. NS

- Merchant Mariners (1915) Yarmouth, NS

- Canadian Forestry Corps - Non Yarmouth Birth/Residence Enlistments

- US Draft Registry - Yarmouth NS Born

- World War II - Menu

- WWII Stories and Articles

- Telegraphist Air Gunners

- WWII Casualties of Nova Scotia

- US Casualties with NS Connection

- Far East/Pacific Casualties with NS Connection

- Merchant Navy Casualties Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia WWII Casualties Holten Canadian War Cemetery

- D-Day Casualties - Nova Scotia

- CANLOAN Program Casualties - Nova Scotia

- Battle of the Bulge Casualties - Nova Scotia

- WWII Casualties Yarmouth NS

- Yarmouth Casualties - RCAF RAF Canadian Army WWII

- Yarmouth Co., Marrages WWII

- Casualties Non-Born/Residents with Connection to Yarmouth Co., Nova Scotia.

- WWII Casualties Digby Co., NS

- Non-Nova Scotian WWII Casualties Buried in Nova Scotia

- WWII RCAF Casualties Aged 16-18

- Brothers/Sisters Who Served - World War II