Story Archive

Wartime Heritage

ASSOCIATION

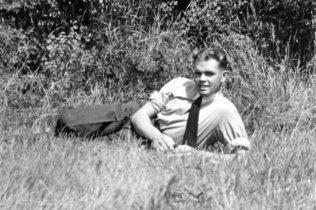

G. J. (Gerry) Lyons was born in Horndon-on-the-Hill, Essex, England on November 6, 1921. He was the son of Denis and

Annie (Graves) Lyons. He had two brothers, Dennis,and Patrick, and three sisters, Eileen, Aileen, and Molly

My Story of #34 Operational Training Unit, Royal Air Force

My story begins in March 1942, two years and a half after WW2 started. We had our early days of Dunkirk,

the phony war, the blitz, Battle of Britain and the start of Bomber Commands penetration into enemy

territory.

Then came word of a posting to RAF PDC Blackpool to prepare for duty overseas. Two weeks embarkation

leave and then we were on our way to form up a unit to be an Operational Training Unit, somewhere.

In Blackpool we came together for medicals, FFI’s (Short Arms), indoctrination and inoculations. There were

people of all trades; Administration, General Duties, Cooks, Service Police, Aircraft Technicians, Supply and

some pilots. In fact every type and trade to make up a complete and functional unit.

Most of us had gone through our trade training courses and had been serving on operational RAF Stations in

Britain since the outbreak of war and were able and willing to get going.

So then, off to Scotland to board the infamous Polish Luxury Liner, MS Batory” which was

to be our transportation to wherever we were going. I will always remember an officer

yelling as we boarded ship ‘250 more bodies down here’. This being the first time I can

remember being treated as cattle and not a person. Anyway, we proceeded to what was

to be our quarters for the next ten days, which turned out to be what was once a

swimming pool, way down below decks. Here all 250 of us were to eat and sleep in tiers

of four i.e. floor, bench, table and hammock. Of course after the first night at sea, it was

soon established who would be on the floor and who would be in the hammock, because

if you were a poor sailor and was sleeping up ton, the poor guy at the bottom got it all. I

think I must have been the first airman to be seasick on the trip, and it must have been

before the Captain ordered the anchor pulled up. Then for the next four days, those of us that were seasick, did not care weather we

lived or died, and grew to dislike the people that would stand over our miserable bodies and talk about greasy pork and other such

horrible foods which would make us head to the ships rail and feed the fish. But after the first four days of misery were over, the next

six at sea were not so bad. We did however, have some Nazi submarine problems, and although we were only two troopships and two

destroyers and moved quite fast, they kept an evil eye on us. When the destroyers dropped depth charges in close to our ship, we

knew how close they were. When these charges detonated we were below decks and below the waterline, the blasts sounded like

hell. The sight of 250 bodies all trying to get out through one small exit, was nerve-racking. God knows how many would have made it

if we had been hit.

Then we were finally informed where we were going, Canada, and also that the last 1000 miles into the port of Halifax, would be the

most dangerous , as enemy subs concentrated in that zone awaiting convoys leaving for the UK.

We wondered what Canada was all about. Most of us only studied about that country in school and could only think of prairies, wheat

and cowboys. But, we were excited about our adventure into this new land.

Then the first sights and sounds of Halifax and Canada as we sailed up the harbour. We saw for the first time since September 1939 a

city with all of its lights on and no black out. Then the sound of an unfamiliar train bell clanging in the distance, a change from the

whistle of British trains.

We berthed at dockside and disembarked to board a train which then shunted out to Rockingham siding siding, and we were served

our first Canadian meal, and what a meal after RAF fare. I will always remember the canned peaches, which was a luxury beyond all

dreams. After the meal we knew that we would love Canada.

A briefing followed about our trip to the town of Yarmouth and a new RAF Station. We were told that we would arrive in Yarmouth at

approximately 0800 hrs. to be met by the Major and the town band, a real welcome. So we had to shine our brass and polish our

boots to be ready for this great ceremony.

Our troops train was made up of old immigrant couches, not the most luxurious, but so much better than our accommodations aboard

the ship MS Batory.

Our all night trip down the south shore was an experience to remember. It seemed that we were going forward and backwards rather

than in one direction as was expected with a train. It appeared, as we found out later, that we were shunting in and out of south

shore towns such as Bridgewater, Liverpool, Mahone Bay, Lunenburg, Lockport etc., dropping off and picking up freight and mail. It

was a long and bumpy trip.

Finally, arriving at Arcadia crossing at approximately 0800 hrs. on Saturday, April 18. No Mayor, no town band, not even a town just

trees, open spaces and mud. Our spit and polish was in vain.

We were unloaded from the train and commenced to march into East Camp, which was still incomplete, no plumbing, no heat and

muddy roads. The mess halls were not open yet, so no food. Our billets were assigned and most of us tried a balancing act on the

pole over the trench which served as our plumbing, a trench later that was to be the scene of many gallant rescues after mess parties.

By this time we were all very hungry and as the messes were not in operation yet, it

was decided that we would be marched to the West Camp (RCAF) for breakfast. There

we were introduced to eggs, bacon, stewed tomatoes (Red lead) with toast and of

course coffee instead of our traditional tea. This sure touched the spot after shunting

back and forth along the south shore.

Back at East Camp a decision was made to pay us all ten dollars in advance of pay and

let us loose into the town of Yarmouth. So, off we went by any means possible, mostly

‘shanks pony’ our first objective being a shower and a chance to clean our muddy

boots. This we did at the YMCA.

Now, it was time to hit the restaurants to try out Canadian foods and fruit. We started at Diamond Lunch, Metropole Café, Clam Shell,

Wagners Lunch and people were friendly and welcomed us with open arms.

Of course we had to visit the Strand Ballroom, more commonly known as the ‘Race track’ or ‘Snake Pit” before returning to East

Camp.

As this was a Saturday and the banks were closed, store keepers quickly ran out of change for so many ten dollar bills, which in those

days was a large piece of money. So, the bankers had to open up their banks to relieve the problem, so once again, ‘Never was so

much owed by so many, to so few’. Yes, our first full day in Canada was an experience we would never forget, in our young years and

the war seemed so far away.

The next three or four weeks at East Camp and 34 OTU was to be a time of roll calls, fatigues, route marches, in fact, anything to fill

in time as we had no planes and nothing constructive to do. One route march sticks out in my mind. The engineering officer decided

he would take our group on a march through Arcadia and Pleasant Lake. The mistake he made was to place himself in front of the

marching group, consequently, at intervals the boys would jump into the ditches and head back to camp. I am sure that by the time

he reached his objective, he found his ranks had diminished considerably.

In that time, just ten days after our arrival, the first of our group entered into Holy matrimony, only to find that someone had gotten

there first and that his new bride was already serviced and was pregnant. So that match was annuled quickly. Guess this is what

happens when you don’t check our your craft before take off!

I might mention that our commanding officer at this time was Group Captain Evans. He was posted back to the UK to command a

station in Bomber Command. He is mentioned in the book, ‘Bomber Command’. He was a very large man and aircrews were not too

happy about flying with him because he had a problem getting behind the control column because of his size and could not manoeuvre

the aircraft as well as they would have liked. In the book it is mentioned that he decided to fly an operation over enemy territory

which was not required of him as a Station Commander. After just one trip he was awarded the DFC and was quite upset about it as he

felt that others had done so much more and had not been decorated or recognized. He flew just one more operation and his aircraft

was hit by anti-aircraft, and destroyed. Only his navigator survived.

Soon we heard via the ‘grape vine’ down town Yarmouth that our group would be moving to a new station and sure enough, in a few

days we were loaded on the Dominion Atlantic Railway train for Digby and a luxury cruise across the Bay of Fundy aboard the SS

Princess Helene to St. John N.B. From there we travelled by train to the new home of 34 OTU, Pennfield Ridge, a station that had

been vacated, we were told by the RCAF because of the lack of flying days due to so much fog.

Here at least we were to have some aircraft and soon the Lockheed Venturas started to arrive from Burbank California. These were a

larger and more up to date of the Hudson and we had the honor of being the first Commonwealth unit to have them. It was our feeling

that these planes must have been rushed through the assembly line as we found many loose ends, maintenance problems and even

tools in odd places that had been left by the factory workers. These tools may have been a blessing in disguise as we only had British

tool kits, none of which were of any use on an American aircraft. We had spanners, they needed wrenches, we had regular screw-

drivers, they had Philips screw drivers. How we came to hate those star screws, especially when we had nothing to work on them

with. Eventually; however, the kits arrived along with a few spare parts and repair manuals, so at least we were in business.

Th Commonwealth aircrew trainees started to arrive and 34 Operational Training Unit (34 OUT) began to do the job it was organized

for. Crews were put together and sent out on practice bombing raids, usually dropping their practice bombs on the marshes at

Musquash which was set up as a target area. Then navigational cross country trips which would give them an idea of what bombing

operations were all about. The only thing missing were the enemy fighters and flac. These they would get to experience only too

soon when they reached the UK.

August 31, 1942 saw a detachment of about 250 persons shipped back to Yarmouth to form an Armament Training Flight. Hangers #1

and #2 were taken over by this group, one for in-flight training and one for maintenance.

The bombing range was located on and around ‘Rat Island’ in the harbour between East and West Pubnico. A

small group was billeted in the village of West Pubnico to look after the range. I am told that to this day the

local people are finding pieces of practice bombs, and one person recalls that he found an explosive cap as a

young man in high school, which exploded and severely injured his hand.

We of this detachment found that we were hard pushed to find spare parts for the Yarmouth Venturas, so

one aircraft was parked in #2 hanger and used as a Christmas tree, from which we borrowed parts to keep

the other aircraft serviceable. This plane, I understand was still in the hanger at the end of the war and I

suppose it was taken apart and shipped away on trucks.

I recall a big flack when a Ventura turned up with extensive damage to its rear under-belly and the whole

maintenance group were confined to barracks until such time as someone confessed to being responsible. It

was thought that the plane was damaged while on a major maintenance inspection and that a jack had slipped and gone through the

fuselage, but that someone was covering up. Anyway, this was resolved when a pilot remembered that he had taxied over a wheel

barrow on the tarmac. So, the confinement was lifted.

The first real wedding took place in December 1942 when Ernie Wetmore, our parachute basher, took the plunge. This turned out to

be a great marriage as Ernie and his wife had a good sized family after returning to Yarmouth after the war to live.

Later Pip Grantly, Ron Trask, and myself took the plunge and also returned to Yarmouth after the war and we were never sorry. Pip

and I were the best man at each others wedding and we are still arguing as to who was the ‘best’ best man. But the course file helped

to wear the elbows and knees out of our uniforms, so that good old Ron had to make the change. I am sure that he knew what was

going on.

The winter of 1942-1943 was a rough one, very cold, windy and icy to the point at

one time that one had to crawl at tomes on hands and knees to get anywhere.

Someone came up with the idea of making metal creepers from galvanized pipe which

we tied to our boots and sure helped one to manoeuvre.

We had one major crash of Ventura #AE932 on December 15th, 1942 which went

down at Caledonia on a supply flight. The crew were all killed and the RAF people, a

pilot and a fitter were buried in Mountain Cemetery. The other crew members

bodies, being Canadian, were shipped to their home towns for burial.

We had some small prangs when undercarriages collapsed on take off. I remember

one crew member getting so excited that he pulled his parachute rip-cord in the plane, much to Parachute Ernie’s disgust.

A very memorable crash was that of an RCAF operational Hudson which crashed on take-off on the runway parallel with Starrs Road.

This was loaded with depth charges and they exploded just as the fire truck people arrived on the scene. The crew off the aircraft

and all of the fire truck people were killed. There could have been many more casualties as many airmen ran to the crash to see if

they could help. An order was issued after this stating that anyone, other than trained rescue people that rushed to a crash would be

put on charge.

Our detached flight worked out very well and a great deal of operational training was accomplished until April 1943 when we were

shipped back to RAF Pennfield Ridge.

A new Commanding Officer had taken over when we returned. He was Group Captain A. Leach M.C. A great Co that liked to mix with

all ranks and one would meet him in any of the messes and canteens. he would just as likely to be having a beer with the airmen and

enjoying it. He was well liked by all which made for a well run station.

Those of us that were married in Yarmouth obtained ‘Sleeping Out Passes” and moved into apartments in St. George which was only a

short distance by bus from the station.

Here we served on a very well organized and active station with many hundreds of Commonwealth aircrews passing through.

One highlight was a visit by Wing Commander Guy Gibson VC of Dam-Buster fame who was touring bases throughout Canada giving

‘pep’ talks. We were saddened to hear that shortly after returning to the UK he was posted as missing in action.

Then came the spring of 1944 and our unit started to break up and personnel were being shipped back to England. By this time there

were plenty of trained aircrews as the war was going well in favour of the Allies in Europe, so our job in Canada was done. Our group

was shipped by train to RCAF Moncton. Then to New York to board ship for our trip across the Atlantic. Our crossing was not too

exciting as the Battle of the Atlantic had been won and D-Day was about to take place.

We arrived at the port of Liverpool and then to Morecombe Lancashire to be dispersed throughout the RAF Stations in the UK and

Europe most of us never to meet again.

So ends my story of 34 Operational Training Unit, Royal Air Force.

Gerry Lyons served six and a half years in World War II in the Essex Regiment and the Royal Air

Force. After the war he returned to Yarmouth Nova Scotia where he was a successful merchant who

owned and operated Lyons of Arcadia Ltd. for 32 years as well as Paul Revere Antiques for 20 years.

He was appointed Area Officer (Air) Nova Scotia by Maritime Command Headquarters with the rank

of Lieutenant Colonel to serve a three year term with responsibility of all Air Cadet Squadrons in the

Province of Nova Scotia.

He died on November 1, 2012 at home in Arcadia, Yarmouth Co., Nova Scotia.

During his life he received the following awards:

- Inducted into Yarmouth and County Sports Hall of Fame (2002)

- Queens Commission 1965;

- Commemorative-Medal for the 125th Anniversary of Confederation of Canada;

- Melvin Jones Award (Melvin Jones Founder of Lions). This is the highest award for past District

Governor, the first awarded in Canada

He was member of:

- Saint Ambrose Cathedral Parish Council for 7 years;

- Villa St. Joseph-du-Lac Advisory Board for 13 years and Chairman of the Board for 8 years;

- Yarmouth Board of Trade;

- Knights of Columbus Member - 4th Degree (Life Member).

He volunteered in the following:

- Scoutmaster 7th Yarmouth Troops (Saint Ambrose);

- Chairman Board of Trustees-Arcadia Consolidated School;

- Chairman of the Fund-raising Committee of Yarmouth’s first ice rink in 1960;

- Co-Chairman of the Yarmouth Y.M.C.A. Swimming Pool fund-raising drive;

- Director of the Y.M.C.A. Board of Yarmouth;

- Served on the International Tuna Match Committee;

- President of Yarmouth and Valley Industrial Hockey League.

- A Charter Member of the Yarmouth Lions Club 1956.

Gerry was married to Jeanette (d’Entremont) Lyons. He had two sons, David and Brian.

G. J. (Gerry) Lyons - #34 Operational Training Unit, Royal Air Force

Photos:

copyright © Wartime Heritage Association

Website hosting courtesy of Register.com - a web.com company

G. J. (Gerry) Lyons

#34 Operational Training Unit,

Royal Air Force

- World War I - Menu

- WWI Stories and Articles

- Photos - Yarmouth Soldiers

- Selection of World War I Songs

- WWI Casualties of Yarmouth, NS

- Those Who Served - Yarmouth, NS

- WWI Casualties Digby Co. NS

- WWI Casualties Shelburne Co. NS

- Merchant Mariners (1915) Yarmouth, NS

- Canadian Forestry Corps - Non Yarmouth Birth/Residence Enlistments

- US Draft Registry - Yarmouth NS Born

- World War II - Menu

- WWII Stories and Articles

- Telegraphist Air Gunners

- WWII Casualties of Nova Scotia

- US Casualties with NS Connection

- Far East/Pacific Casualties with NS Connection

- Merchant Navy Casualties Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia WWII Casualties Holten Canadian War Cemetery

- D-Day Casualties - Nova Scotia

- CANLOAN Program Casualties - Nova Scotia

- Battle of the Bulge Casualties - Nova Scotia

- WWII Casualties Yarmouth NS

- Yarmouth Casualties - RCAF RAF Canadian Army WWII

- Yarmouth Co., Marrages WWII

- Casualties Non-Born/Residents with Connection to Yarmouth Co., Nova Scotia.

- WWII Casualties Digby Co., NS

- Non-Nova Scotian WWII Casualties Buried in Nova Scotia

- WWII RCAF Casualties Aged 16-18

- Brothers/Sisters Who Served - World War II