Wartime Heritage

ASSOCIATION

copyright © Wartime Heritage Association

Website hosting courtesy of Register.com - a web.com company

Memories of Groningen Liberation 1945

Bonnie van der Meulen-Hiddema

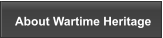

It was the final days of war in Europe. On April 13, 1945, the 2nd Canadian Division began the liberation of Groningen, a city in

northern Netherlands.

The inner city of Groningen had narrow streets lined with

apartments and buildings and completely enclosed by a wide

canal. Twelve bridges were the only access and many of the

bridges had been destroyed, or simply raised by the Germans

to render them inoperative. The city had several canals

entering from the south and the west, which were obstacles

to movement for soldiers approaching from those directions.

Two large defended municipal parks dominated the western

and southern approaches to the city, and there were several

tall water towers, factories, and church spires which were

enemy observation posts and weapons emplacements.

On the evening of April 13th, the 5th Canadian Infantry

Brigade, consisting of the Black Watch (Royal Highland

Regiment) of Canada, Le Regiment de Maisonneuve, and the

Calgary Highlanders and 5th Brigade entered the town from

the west.

On April 14th, the 4th Canadian Brigade managed to penetrate

the southwest outskirts, resulting in house-to-house fighting.

The 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade, Les Fusiliers Mont Royal,

the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, and the

South Saskatchewan Regiment moved through the opening

created by the 4th Brigade and entered the city center on

April 15th.

The following day the German defenders surrendered.

Bonnie van der Meulen-Hiddema (1927 - 2014)

Bonnie van der Meulen-Hiddema was born in Groningen, Netherlands on

November 14, 1927, the daughter of Tjeerd Hiddema and Maaike Kuipers. She

had two older brothers, Rein (b. 1923) and Watze (b. 1925) and a younger sister

Aukje (b. 1929).

Bonnie obtained her medical degree in 1953, in Groningen and started to work in

a psychiatric hospital. In 1955, she married Folkert van der Meulen, a Baptist

Minister. They lived in Ternaard, a very small village in the north of the

Netherlands, and from 1955 until 1960, Bonnie worked as a teacher.

In 1960, the family moved when Folkert obtained a job in Amsterdam. In 1964

Bonnie found work as a medical doctor in Amsterdam. She did gynaecological

work, sometimes psychotherapy. After her retirement in 1992, she volunteered

in a large hospital as a physician.

Bonnie and Folkert were the parents of five children, 1956 Marit (b. 1956), Jaap

(b. 1957), Moon (b. 1959), Harke Jan (b. 1962), and Klaske (b. 1964). They made

clear to their children the importance of peace and how terrible the

consequences of war. The importance of remembering the war years has passed

on to their children.

Bonnie van der Meulen-Hiddema was a seventeen-year girl in April of 1945 and

the soldiers she met, although only for a few days, made an impression on her that endured her whole life.

The war years, the liberation of Groningen, her thoughts and memories of 1940 through 1945, would become a

book she would write and publish in 2010.

The following is an English translation excerpt from her book “Little Bob and many others - The years 40-45 Through the Eyes of a

Growing Girl” published in 2010. Bonnie van der Meulen-Hiddema was a seventeen-year girl that April and the events of the

liberation would become part of a book she would write in the years after the war.

“We never knew what crimes the Germans committed in the last days of the war. Hannie Schaft and painter Werkman were

killed in those days. How is it possible we did not know?

It is difficult to describe the atmosphere. We felt guilty because the Canadians had to liberate us risking their own lives. We

felt insecure and worried about all the people who had disappeared. About our nephew Sibbe, Martje’s husband. We never heard

anything more about him. I prayed to God every night to protect him.

But at the same time, we were excited about the coming liberation.

It was mid-April 1945. It was beautiful weather at the time. It was so warm we were lying in the sun on top of the roof of the

kitchen. Maybe we heard the clash of arms, I cannot remember. It might be my imagination. However, I am quite sure of the shell

burst on April 13, 1945. There were no casualties, only part of the roof of a house in our street [Adelheidstrat] had been damaged.

Apart from this nothing had happened, but we were not allowed to go out of the house. We all slept in rows on the floor of our

living room. Corrie Sparreboom slept between us.

I cannot remember what happened the Saturday following. Nothing was happening in our neighbourhood. We stayed indoors.

On Sunday morning everything changed. Near our house used to be a water tower. These water towers no longer exist. In those days

the height of the water tower defined to what height the water in the houses could reach, in accordance with the principle of

communicating vessels. So, there was a lot of water up in the water tower. The first thing we saw on that Sunday morning was the

enormous flow of water coming out of the water tower. A Canadian regiment called the black watch – our liberators – had hit the

tower and it was a good shot for the water was streaming out. The Germans in the tower could not strike back at the Canadians

because there was water everywhere. My brother Watze told me that the German Defense Command was housed in the Tower so

that was why the Canadians had first hit the tower.

We were watching all this from our bedrooms at the back of the house because this was the side from which the Canadians

were to come. In between was the Reitdiep, a canal on the western side of Groningen.

I shall never forget what I saw then. Somehow a ship had managed to move crosswise the canal. The Canadians were moving

from one side of the canal across the ship to our side of the canal. They could not cross the canal by the bridge because it had been

closed by the Germans. From then they were very soon in our streets. We were so excited, all of us.

Within no time the first Canadian was in our room. He had come to us obviously to show us that the street was in their hands.

There was no fighting because there were no Germans in our street. I can still see him sitting in the comfortable chair. We had not

much to offer him. He had cigarettes and chocolate to offer us. The name of the cigarettes was “Sweet Caporal” but that was not

important. We were deeply impressed by his presence and his story (our English was not good, a little bit of a problem).

He had volunteered for military service shortly before the war “but after a fortnight I was sorry”. His name was Frank B

Richards, he was called Ritchie, 21 years old. We were all sitting around him, the neighbours too, Mrs. Blazer and Eusje and Simon.

He gave us a photograph of himself of which his sister had been cut off. We could not believe this was happening; it was almost

beyond our comprehension. My image was cut from a photograph for him.

He was the first to give us the poem of the soldier who had fought in Italy; later we saw this poem everywhere:

In the afternoon he had left again. The bridge across the Reitdiep was open again. We thought the Germans had left. We were

so excited and left our house. We came to Prinsesseweg, a side street to ours, a much broader street. My brother Rein was so

happy to be out in the streets. But I thought Prinsesseweg was a bit scary. The Canadian soldiers were hiding out, but we were still

walking there out in the open.

At the end of the street was the bridge that was now open. We wanted to cross it. This is what we did: We came into Herman

Colleniusstraat. We passed the water tower out of which water was still streaming. We were reaching the crossroads with

Wassenbergstraat. At that moment I looked back over my shoulder, and I saw a Canadian soldier sitting in a house on the first floor

in an open window ready to shoot. I was really scared by this and I realized we were doing something very dangerous. We ran back

to our house although it would have been safer to stay with the people there. We came home unharmed. But we had taken a very

big risk. Jelle Gerritsma’s father had been hit by a bullet on Wassenbergstraat and had died. At night we looked over the city, it

was a sea of fire.

That night Ritchie was to sleep at our place. The house was very full. We made room for him of course. Ritchie was to sleep

in the large bed that Aukje and I used to share. Aukje, Cobi, and I slept the three of us in a single bed in my parents’ bedroom. We

did not sleep much that night. But we wanted to give him a good bed. “Oh what a soft bed”, he said to mum as she showed him his

bed.

Next day was Monday. I cannot remember at what time he left. In the evening we heard he had been quartered in het RIJKS

HBS (a national school for secondary education). We went there with too many people. Everyone wanted to come of course. It was

so wonderful to walk the streets again . We saw Ritchie standing near the building where he had been quartered. We talked to him

but there were too many of us and we were not used to speaking English. I still feel sorry it went like this. I even feel ashamed. We

were laughing a bit, but I did not really want to. He was in a difficult position in the war, far away from his home.

Eusje Blazer and Aukje were there too. We could not do much for our Canadian soldier. We did not ask him anything. We did

not know how. Did he want to tell us something there? I felt uncomfortable, even a little in love with him. I felt sorry for him

because he had to go on fighting in the war. I did not know how to hold the conversation; I did not last very long I am afraid.

The next morning on April 17th my brother Watze went into

town. People were allowed too now. He came back totally impressed

because the centre was in ruins. The Stoeldraaiersstraat was

completely devastated, the Grote Markt was severely damaged too.

There was no more shooting, the Germans were nowhere. I saw one or

two in a park, completely harmless.

We were told that Tuesday morning that the troops that had

liberated us were to leave. Earlier that day I saw a French speaking

unit attending a religious service in a park. They were saying the

rosary. They were Canadians too. In the afternoon Ritchie was to

leave by car. I just managed to say goodbye to him before they left.

I was walking home. I came on Oranjesingel, along the house of

Mrs. Reinders, where I had always secretly collected my news

reports. I was alone. I wore a red cardigan that had been knitted from two different sorts of red coloured wool. Ritchie had gone.

He had to go to Delfzijl. Maybe he was to fight again? “Let him please be safe”. So much had happened these past four days, it was

past imagination.

The thoughts were not in my head. Still, they were there, somewhere around me. They accompanied me while I was walking.

Everything that had happened came with me. Ritchie had liberated us, and he had left again. And there was me, walking. I was a

woman, seventeen years old, in a red cardigan, walking, not alone, but with everything, not thinking, feeling alone, but feeling

good, everything was OK. Yes, this was how it was, this was how I was walking there.

Two weeks later I was suffering from jaundice. I felt very sick at first. I came out of school which was back at our own building

on Hofstraat. On the way home I saw Canadian soldiers on Guyotplein, but I was too ill to see them as I would like to see them, as

people with whom you would like to share your feelings of joy. How? It was just a feeling.

On Guyotplein was an institute for people with hearing problems, now soldiers had been quartered there. It was impossible

for me to feel my belonging to the Canadians. I felt simply too ill. When I came home, I went straight to bed. Mum wanted to give

me something to eat, but I could not eat any more. I had to have glucose, dextropur it was called. When I got better, I wrote a letter

to Ritchie.

We had been liberated. Our first impressions with the tanks and the jeeps were so overwhelming. To have been finally so

lucky. We could hardly cope with it. Everywhere in town people were celebrating, every street had its own feast, everybody

dancing. We made new songs. This was one of them:

You put your whole self in

You put your whole self in

You put your whole self in

And you shake it in and out

You do the hokey pokey

And you turn all around

And that’s what’s all about

With this song we were to turn inside and outside and finally turn around, very rhythmically, repeating ten times. After a few

weeks the feats were no fun any more.

The Canadians stayed on for another six months in Groningen. I never saw Ritchie. In every Canadian I saw I hoped to see him,

but it was never him.

We never heard anything more from Ritchie. Many years later I found out that he had returned to Canada after the war.

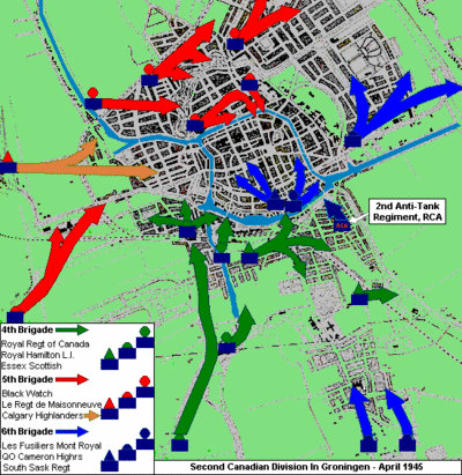

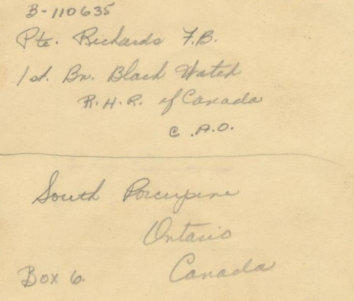

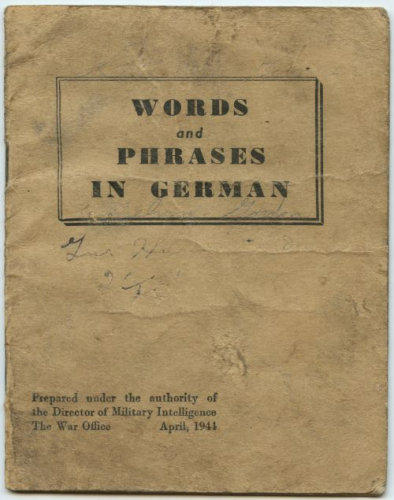

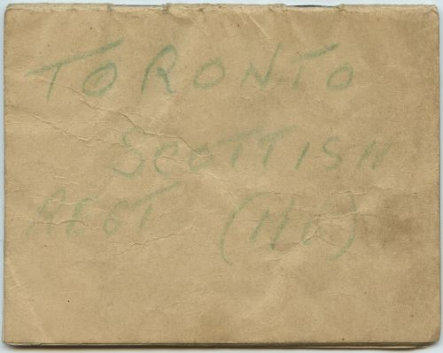

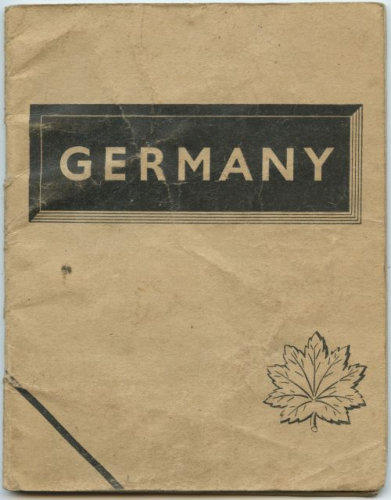

The photos below are of treasured wartime keepsakes from the time of liberation. The books were signed by Canadian soldiers.

Frank B Richards “Richie”

Look God, I have never spoken to You

But Now I want to say: How do You do?

You see, God, they told me You did not exist,

And like a fool, I believed all this.

Last night from a shell hole I saw your sky –

I figured right then they had told a lie,

Had I taken time to see things You made,

I’d have known they weren’t calling a spade a spade.

I wonder, God, if You’d shake my hand:

Somehow, I feel that you will understand.

Funny I had to come to this hellish place.

Before I had time to see Your face.

Well, I guess there is not much more to say,

But I am sure glad, God, I met You today,

I guess the zero hour will soon be near.

But I am not afraid since I know You are here.

The signal! Well God, I will have to go;

I like You lots, this I want You to know.

Look, now, this will be a horrible fight.

Who knows, I may come to Your house tonight.

Though I was not friendly to You before,

I wonder, God, if You’d wait at Your door.

Look, I am crying! Me. Shedding tears –

I wish I had known You these many years.

Well, I have to go now, God, Goodbye!

Strange, since I met You, I am not afraid to die.

CYRIL RAYNOLD ATWELL was born in the small village of Melanson, Kings County, Nova Scotia, on September 16, 1923.

The village is located just outside of the town of Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Returning from overseas at the end of the war he

was employed as a carpenter. He had a sister living in Ontario and he lived for a time in Hamilton, Ontario where he

married Jeannie Marie St. Jean. In December 1952 they moved to California in the United States. He was 28 years of

age, 5 feet, 11 inches in height, medium complexion, brown eyes, and brown hair.

At some point they returned to Canada and in 1972 were living in the Fraser Valley, British Columbia. He was employed as

a carpenter. His wife died on February 11, 1973, in British Columbia. Cyril died in December 1976 in Yuma, Arizona, in

the United States. Both are buried in British Columbia.

As part of the 2nd Infantry Division, the Toronto Scottish

Regiment (machine guns) fought in Groningen and North-West

until the end of the war.

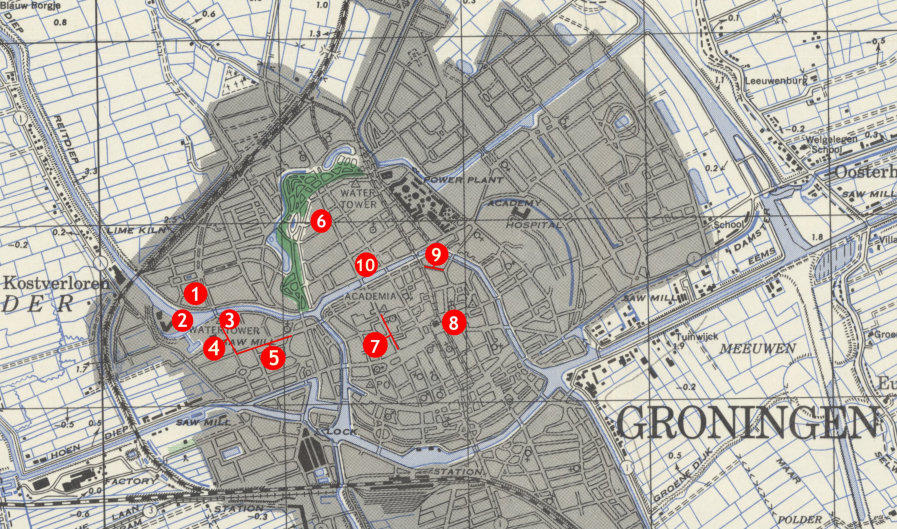

Location of streets and places referred

to in the article:

1 - Adelheidstraat

2 - Reitdiep Canal

3 - Watertower

4 - Hermanberghstaat

5 - Wassenbergstraat

6 - RIJKS HBS

7 - Stoeldraaiersstraat

8 - Grote Markt

9 - Hofstraat

10 - Guyotplein

Photo of Bonnie van der Meulen-Hiddema, excerpt from the book,

and photos of wartime keepsakes courtesy of Marit van der Meulen.

- World War I - Menu

- WWI Stories and Articles

- Photos - Yarmouth Soldiers

- Selection of World War I Songs

- WWI Casualties of Yarmouth, NS

- Those Who Served - Yarmouth, NS

- WWI Casualties Digby Co. NS

- WWI Casualties Shelburne Co. NS

- Merchant Mariners (1915) Yarmouth, NS

- Canadian Forestry Corps - Non Yarmouth Birth/Residence Enlistments

- US Draft Registry - Yarmouth NS Born

- World War II - Menu

- WWII Stories and Articles

- Telegraphist Air Gunners

- WWII Casualties of Nova Scotia

- US Casualties with NS Connection

- Far East/Pacific Casualties with NS Connection

- Merchant Navy Casualties Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia WWII Casualties Holten Canadian War Cemetery

- D-Day Casualties - Nova Scotia

- CANLOAN Program Casualties - Nova Scotia

- Battle of the Bulge Casualties - Nova Scotia

- WWII Casualties Yarmouth NS

- Yarmouth Casualties - RCAF RAF Canadian Army WWII

- Yarmouth Co., Marrages WWII

- Casualties Non-Born/Residents with Connection to Yarmouth Co., Nova Scotia.

- WWII Casualties Digby Co., NS

- Non-Nova Scotian WWII Casualties Buried in Nova Scotia

- WWII RCAF Casualties Aged 16-18

- Brothers/Sisters Who Served - World War II