Wartime Heritage

ASSOCIATION

copyright © Wartime Heritage Association

Website hosting courtesy of Register.com - a web.com company

Ringing in the New Year

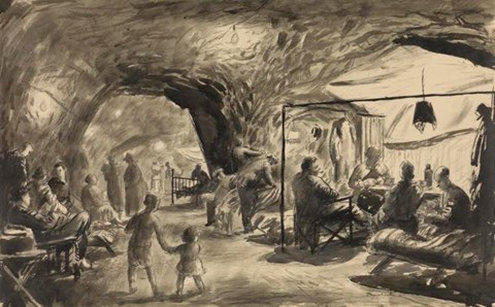

Chislehurst Caves -1941

Ringing in the New Year

Chislehurst Caves 1941

Eighty years ago, for thousands of British people, the Chislehurst Caves were their home during the air raids and bombings by

enemy German aircraft. The caves had been used to store ammunition during the First World War, and to grow mushrooms in the

1930’s. They were not natural caverns – they were dug out when being used as a chalk mine – all 22 miles of them, a hundred feet

underground.

When the Second World War began in 1939, anxious locals had broken in to the caves to use them as an emergency shelter.

By the time of the Blitz, the caves had electric lights, running water and an air ventilation system. A team of men were paid as a

sanitation squad to maintain the latrines. People came from across London and north west Kent to shelter there. At the height of

the bombardment between October 1940 and July 1941, thousands used the cave system each night, which also included a chapel

and a hospital.

An American journalist wrote in October 1940, "In little niches decorated as rooms, they [families] put up beds with spring

mattresses, light their portable stoves and cook the evening meal.”

"Afterwards the dishes are stacked, the wife knits; the father reads the newspaper and the children play in the street."

An interesting account of New Year’s Eve, 1941 was published by New York Herald Tribune, European Edition, on January 1,

1941:

“1941: Ringing In the New Year, Underground”

“In many different parts of England at the stroke

of midnight the faint sound of laughter and singing

could be heard issuing from deep in the earth. These

waves of sound, vanishing and swelling in turn, came

from thousands of people who, like their primitive

ancestors, have taken to the caves of England for

protection, warmth and human companionship.

Wherever there is a cave that is reasonably dry —

and there are fifty or more large ones — they are

crowded with men, women and children of all ages,

families of two to fourteen persons, who have lost

their homes or have lived in rickety houses too close to

military objectives for comfort and sleep. I visited one

of these huge caves last night. In a suburban

community not far from London I stepped through a

dark hole in the side of a hill and found myself in a narrow passageway resembling the entrance of a draft mine. An electric-light

bulb cast a dim glow on the rocky ceiling and walls of the corridor.

As I picked my way warily along the passage, the singing and shouting I had heard long before I neared the mouth of the

cave grew louder. Suddenly I found myself in the main cabin. All around the walls the people were packed tight, sleeping children

around them, their mouths wide open as they sang a popular tune played by two men and a girl with a banjo, guitar and

concertina.

Ten thousand people, I was told by a shelter warden, were greeting the New Year in this one labyrinthine cave, 100 feet

under the ground. They were all in the reaches and corridors, which stretched for miles into the rock; for months they had made

their homes here at night, and they will continue to do so for some months to come. They like their cave when German bombers

rain death and fire onto the earth above them. They are safe, in fact, they hardly hear a thing, and so sleep peacefully.”

Art by Henry Carr © IWM Art.IWM ART LD 967

Chislehurst Caves WWII

Mary Evans Picture Library

Wartime whist drive (card game) in Chislehurst Caves

Mothers in bunks and babies in cots deep underground in their

cave shelter, where tey find peace and respite from the flying

bombs

- World War I - Menu

- WWI Stories and Articles

- Photos - Yarmouth Soldiers

- Selection of World War I Songs

- WWI Casualties of Yarmouth, NS

- Those Who Served - Yarmouth, NS

- WWI Casualties Digby Co. NS

- WWI Casualties Shelburne Co. NS

- Merchant Mariners (1915) Yarmouth, NS

- Canadian Forestry Corps - Non Yarmouth Birth/Residence Enlistments

- US Draft Registry - Yarmouth NS Born

- World War II - Menu

- WWII Stories and Articles

- Telegraphist Air Gunners

- WWII Casualties of Nova Scotia

- US Casualties with NS Connection

- Far East/Pacific Casualties with NS Connection

- Merchant Navy Casualties Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia WWII Casualties Holten Canadian War Cemetery

- D-Day Casualties - Nova Scotia

- CANLOAN Program Casualties - Nova Scotia

- Battle of the Bulge Casualties - Nova Scotia

- WWII Casualties Yarmouth NS

- Yarmouth Casualties - RCAF RAF Canadian Army WWII

- Yarmouth Co., Marrages WWII

- Casualties Non-Born/Residents with Connection to Yarmouth Co., Nova Scotia.

- WWII Casualties Digby Co., NS

- Non-Nova Scotian WWII Casualties Buried in Nova Scotia

- WWII RCAF Casualties Aged 16-18

- Brothers/Sisters Who Served - World War II